Antarctic 2011

The Falklands, South Georgia,

and the Antarctic Peninsula

Trip Report

For the fourth time in eight years, Mary and I joined Joseph Van Os Photo Safaris as part of the photo leader team for a lengthy photo expedition to three of the most spectacular wildlife and landscape locations in the Southern Hemisphere. This year’s trip to the great South was characterized by real adventure, experiences we’d not had in any of our three previous trips to the southern seas. These highlights included a zodiac flipped over by high winds, with, fortunately, only the boat sailor aboard and whom was rescued; an attack by an Antarctic Fur Seal that I stopped by shoving my tripod-mounted camera in its face (the same seal later bit one of our other trip leaders); and a turbulent cruise through the Drake Passage in near hurricane-force waves.

We’d hoped for snowy landscapes, starting the trip at least a week earlier than any previous trip we’d made, but almost all of our precipitation was rain, which bodes unsettlingly for a global climate change or warming. Still, experiences and photographs were varied and spectacular, and included Antarctic Fur Seals that crowded many of the beaches of South Georgia; Elephant Seals that were finishing up most of their mating activity; and penguins that were busy laying eggs and/or incubating. One of our zodiacs had an incredible experience with the South’s ultimate predator, a Leopard Seal, that actually punctured one of the air compartments of that zodiac as it played with, or attacked, the zodiac, providing some excitement in addition to some stunning photo opportunities.

The following is the day-by-day account of the trip, providing a bit more depth to the experience. Enjoy.

Day 1 – 2.

Travel days, with an arrival into Ushia, the southernmost city in the world where one of our four pieces of luggage did not arrive with us. Fortunately our luggage, and that of two other participants of the trip, arrived and our boarding of the boat proceeded uneventfully. That evening, and the following day we cruised almost lake-like waters, making incredible time as we headed toward New Island, one of the westernmost islands in the Falkland Island archipelago.

Day 3. New Island.

Day 3. New Island.

We arrived around midnight, anchored, and awoke to partly cloudy skies, no wind, and fairly warm temperatures. New Island has a large Gentoo colony improbably located along one of the highest points of the grassy hillsides, several hundred feet above the water. The main attraction, however, is the large Black-browed Albatross and Rock-hopper Penguin colony located on the opposite side of the isthmus where we anchored. Nearly everyone, despite age or weight, made the mile long walk to the colonies, which began, intimidatingly enough, with a steep  70 foot embankment. Once over that crest the rest of the hike is a fairly easy uphill trek along an old jeep trail. En route, Striated Caracaras flew down to investigate and, later, flew in to snatch as many as twenty Upland Goose chicks, sometimes wiping out an entire clutch.

70 foot embankment. Once over that crest the rest of the hike is a fairly easy uphill trek along an old jeep trail. En route, Striated Caracaras flew down to investigate and, later, flew in to snatch as many as twenty Upland Goose chicks, sometimes wiping out an entire clutch.

None of the nesting birds had chicks, and not all had eggs, and patient Albatrosses sat quietly on their mounded nest, awaiting mates or the arrival of an egg. Occasionally a caracara would hop in, trying to steal an egg, and occasionally being successful. Peale’s Dolphins plied the waters far below, their black and white pattern resembling a miniature orca, and King Cormorants periodically flew in, carrying nesting material for their nests, located in a deep crevice.

The day started cool and partly cloudy but by day’s end the skies were cloudless and the afternoon was warm. A slight breeze picked up, giving lift for albatrosses that, earlier in the day, sat virtually motionless on their nest mounds. To arrive at a colony of albatrosses, and seeing none in flight, is a bit deflating, and boring, as their glides across the sky and landscape give incredible energy to the scene. By the end of the day, however, some birds were flying, and Mary and I and John challenged ourselves, capturing white birds against the backdrop of coal black cliffs. The group headed back some time after 5, with our last departure from a still calm beach by 6:30, with plenty of happy but very tired photographers.

The day started cool and partly cloudy but by day’s end the skies were cloudless and the afternoon was warm. A slight breeze picked up, giving lift for albatrosses that, earlier in the day, sat virtually motionless on their nest mounds. To arrive at a colony of albatrosses, and seeing none in flight, is a bit deflating, and boring, as their glides across the sky and landscape give incredible energy to the scene. By the end of the day, however, some birds were flying, and Mary and I and John challenged ourselves, capturing white birds against the backdrop of coal black cliffs. The group headed back some time after 5, with our last departure from a still calm beach by 6:30, with plenty of happy but very tired photographers.

Day 4, AM. West Point Island

Day 4, AM. West Point Island

We arrived on WPI by 8:30 under incredibly blue skies and a calm wind. WPI features a ‘settlement,’ what was once a sheep farm and is now a homestead with limited sheep and cattle raising and a catering to tourists, where songbirds, caracaras, and geese cluster close by. A very long walk away there is a Black-browed Albatross and Rock-hopper Penguin colony and, after we unloaded everyone, I hitched a ride with the land care-taker and with several others headed across the moorland to the colony. En route we passed several participants that took the hike, which I avoided without shame with a bad back. The caretaker took me about, showing where to go and where not to, and I was stunned by the proximity of the birds – albatrosses where perched literally beside the trail. He also pointed out a peninsula-like spit of land where he said some photographers go, via a circuitous route that skirted the colony but that required negotiating a narrow spine of land where, on either side, steep cliffs dropped to the sea. With some reluctance I had planned on taking some of the more enthusiastic shooters there, but as I scouted it out later I noticed the albatrosses were nesting all along the spine, making it almost impossible to travel without disturbing the birds. Consequently, I apologized and passed on this.

We spent a good part of the morning photographing albatrosses in flight, especially using slow shutter speeds where I panned. Mary worked on the beach the entire time, photographing flying Kelp Geese, Falkland Thrushes, Turkey Vultures, and more. I stayed at the colony, and as of now I haven’t looked at any image, but I imagine the keeper ratio will be small.

We spent a good part of the morning photographing albatrosses in flight, especially using slow shutter speeds where I panned. Mary worked on the beach the entire time, photographing flying Kelp Geese, Falkland Thrushes, Turkey Vultures, and more. I stayed at the colony, and as of now I haven’t looked at any image, but I imagine the keeper ratio will be small.

PM. Graves Beach.

The afternoon grew dreary and by the time we boarded the zodiacs it began to spit rain and, for a few minutes, spotty snow. By the time we reached the beach it was raining hard enough that none of the leaders bothered to pull out camera gear from the dry bags. Most of the participants did photograph, braving the rain as they shot the large Gentoo Penguin colony and the schools of penguins that surfed, dove, and jumped into the beach. Mary and I visited the beach where I ‘pretended’ to shoot, trying to anticipate where I’d have focused a big lens. I’m glad I didn’t, because even in practice I know I was not very successful. Nonetheless we stayed on the beach to 7, and by then the few of us left were cold and very damp. Ironically, when we returned to the boat I got a hot shower but the heating system quit as Mary took her’s, and after a cold day on the beach that was something she didn’t need.

Day 5. Saunders Island

Day 5. Saunders Island

Despite yesterday’s rains the sky was brilliant this morning with almost perfect conditions, warm and windless. Saunder’s features three great shooting opportunities, with perhaps the largest Gentoo Penguin colony in the world, a great haul-out beach and swimming pool for Rock-hopper Penguins, and on the cliffs above, very accessible and open rookeries and mixed colonies of King Cormorants, Black-browed Albatrosses, and Rock-hopper Penguins.

We arrived on the beaches and were ready to disperse by 9, and I took a few photographers up the slopes for the albatross colony. In the near windless conditions the birds, we suspect, were not flying, and so the Rock-hoppers waylaid us for hours, as they marched the several hundred feet from the surf to a little fresh water stream to drink. Large flocks of King Cormorants occasionally soared by, swirling and circling before dropping close by into their nests, mixed among the Rock-hopper Penguins. Many of the birds carried vegetation in their bills, much of it land-based plants and green, leafy algae.

As the morning progressed the winds increased and the albatrosses took flight, circling about to drop back into their nests, their webbed feet flared for breaking and, perhaps, steering. Skuas and Striated Caracaras patrolled the edges, with the skuas occasionally dropping into the colony to steal an unguarded egg.

The afternoon light was perfect for the Rock-hopper swimming pool and birds popping from the surf, their feathers glistening and pristine from the sea, where the birds in small groups hopped up onto the rocks and continued either to the pool or to climb the cliffs to their rookeries. Gentoos continued to amass along the sandy beach, with reflections stretching long across the mirror-like wet sands.

I ended the day with a very cooperative pair of Pied Oystercatchers and, in the last hour on shore, a visit with the owners of Saunders, the Pole-Evans, who we’ve known for years, since film days when we would often spend weeks on photo tours on three of the Falkland Islands.

The visit to Saunders concluded what has probably been our most successful trip to these islands since we started doing these cruises, and with the near perfect light all day I shot nearly over 60 gbs, which translated to almost 3,000 images for the day – there will be some long editing sessions ahead!

Day 6 and 7. At Sea

Day 6 and 7. At Sea

We left the Falklands and continued across the South Atlantic in a following sea, where a west wind helped propel us forward at about 13 knots. The winds, blowing from our backs, produced swells that went with us, so the boat was far more stable than had the winds been blowing from any other direction. We spent the days attending lectures, editing, and shooting birds from the deck. One of the passengers, on Day 7 and early, was out on the upper deck when a rogue wave hit the ship from the side, dousing her in sea water. Fortunately no one was on the lower deck, where the force of that wave could have caused injury or worse.

Unlike our other cruises, virtually no one is sick, and our meals are attended by everyone. We had our first Wandering Albatrosses on Day 6, and on Day 7 both a Light Mantled Sooty and a Gray-headed Albatross passed by. While there is still wind, oddly enough Day 7 was relatively light on birds, with the same two or three wandering albatrosses circling infrequently behind our ship. I never saw an albatross flap, for on stiff winds they soared down almost to water level, sometimes with the trailing edge of a wing streaking the surface, where the upward push of the wind propelled them up again into a high arch where, time and again, this see-saw glide would give them lift, aided by a constant wind. In deal calm and windless seas this required lift is absent, and the air is empty of birds. I’ve seen this on other trips and while the sailing is pleasant the days are long and dull.

Day 8, At Sea and to South Georgia, Landing at Right Whale Bay

Day 8, At Sea and to South Georgia, Landing at Right Whale Bay

The seas were relatively calm and shrouded in a thick fog, and our morning was spent in lectures, followed by a vacuuming session to remove any potential invasive seeds from our clothing and bags. The weather did not improve by the time we anchored in Right Whale Bay, but our landing, often a challenge on South Georgia, went remarkably smooth.

Despite the constant blowing drizzly mist we attempted some photographs, while many of the participants avidly shot away, despite the weather. A bull Elephant Seal rose its forequarters up high repeatedly, snarling its snoring honk with its inflated nasal flap, steam blasting from its maw like smoke from a dragon’s mouth. The beaches are covered with bull Antarctic Fur Seals, on territory and testy, chasing rivals and our participants. Most seal interactions are aggressive bluffs, with males coming together and bobbing and weaving heads, and neck-bumping like pro football players chest bumping after a play. Rarely seals would engage, biting each other’s necks and shaking vigorously.

Despite the constant blowing drizzly mist we attempted some photographs, while many of the participants avidly shot away, despite the weather. A bull Elephant Seal rose its forequarters up high repeatedly, snarling its snoring honk with its inflated nasal flap, steam blasting from its maw like smoke from a dragon’s mouth. The beaches are covered with bull Antarctic Fur Seals, on territory and testy, chasing rivals and our participants. Most seal interactions are aggressive bluffs, with males coming together and bobbing and weaving heads, and neck-bumping like pro football players chest bumping after a play. Rarely seals would engage, biting each other’s necks and shaking vigorously.

King Penguins massed along the beach and huddled in large masses on sloping snow banks, but the light, and the rain, was uninspiring and I went out into the open terrain to  look for shots. I’d just passed a wide open stretch between the seals when a distant bull, fully 50 yards away, suddenly charged me. The seal came on fast, not too fast for me to run from but I held my ground, figuring that the seal would stop. It didn’t, and at the last second I stuck my rain-coated-covered camera in the seal’s face. It stopped, and fortunately didn’t grab my expensive rain gear, but its wide eyes looked around at me in its expressionless aggressive pose, then turned and shambled off.

look for shots. I’d just passed a wide open stretch between the seals when a distant bull, fully 50 yards away, suddenly charged me. The seal came on fast, not too fast for me to run from but I held my ground, figuring that the seal would stop. It didn’t, and at the last second I stuck my rain-coated-covered camera in the seal’s face. It stopped, and fortunately didn’t grab my expensive rain gear, but its wide eyes looked around at me in its expressionless aggressive pose, then turned and shambled off.

Several of our Mexican passengers had seen the charge and were a bit shaken up, but I assured them that if they stood their ground they’d be ok. I should have added that one also needed a blocking instrument of some kind, too.

As I headed back to our landing zone to assist in loading the zodiacs I saw the same seal charge a short distance towards another person, this time one of our trip leaders. He didn’t have a pole or tripod and the seal kept on coming, knocking him down and biting him close to the knee. He kicked at the seal several times and it moved off, but the bite was a good one and required four stitches. It was a sobering reinforcement of the warnings we’d given our passengers about the dangers a fur seal can pose.

Day 9, Salisbury Plains.

Day 9, Salisbury Plains.

The morning was dark and wet as we off-loaded onto the beach of what is one of the most spectacular beaches for King Penguins. Approximately 60,000 pairs nest on the flats and the hillside, and in good weather, the birds and the ring of mountains surrounding the rookery are stunning. Unfortunately, this morning was not that type of day.

Of course, the weather didn’t deter the participants who immediately dug out equipment. The staff, which included Mary and I, were still busy unloading passengers from the zodiacs or blocking aggressive fur seals from coming too close. One came out of the surf and was not intimidated by my bluff, and chased me up the beach for a few yards. We started carrying paddles after that.

By late morning the misting rain had stopped and from our landing zone position Mary and I began to photograph, concentrating on the bunches of King Penguins and the occasional spat of dueling fur seals. We didn’t have long to shoot before the first passengers started lining up for the zodiacs back to the boat.

By late morning the misting rain had stopped and from our landing zone position Mary and I began to photograph, concentrating on the bunches of King Penguins and the occasional spat of dueling fur seals. We didn’t have long to shoot before the first passengers started lining up for the zodiacs back to the boat.

We’d planned on returning to the beach after lunch. Normally we’d have a full non-stop day on Salisbury, but with the bad weather, and the forecast of high winds, we were playing it safe. The skies continued to clear and the weather looked promising, and we planned on a departure at 3. As 3 arrived an unexpected wind developed, the fierce Katabatic winds that can start up unexpectedly and roll down the mountainsides at hurricane force. These winds come from inland, rather than the predicted heavier winds we had worried about that would be coming from the sea. We put off the departure, and watched as the winds only increased, reaching 50 knots or more, powerful enough to flip a zodiac. We waited and watched, the ship’s flag rippling straight in the steady blasting wind, and as 5PM neared we formally cancelled the landing, with no end yet in sight for the cessation of the winds.

Day 10, Prion Island

Day 10, Prion Island

We had a late departure as the fog and rain shrouded Prion Island, but by 9 the light and the fog were high enough for a landing. Prion Island has the only accessible Wandering Albatross nesting site, and since we were here two years ago a boardwalk has been erected that makes access to the top of the island fairly easy. In the past, we made this journey by slogging up a wet and muddy streambed, weaving in and out of tussock grasses. Now, a chicken wire-covered boardwalk leads the way, although the shooting is now restricted completely to the walkway and few platforms.

Only 8 month old, giant chicks were on the nest. These had the white faces of the adults but were otherwise mostly black, with gray down layering their necks. Some birds stretched and flapped their wings, others preened, and, when a heavier rain fell, one raised its beak to the sky to drink. Snow squalls with giant flecks floated down at one point, driving hail or grabble at another, and in between, it mostly rained.

Only 8 month old, giant chicks were on the nest. These had the white faces of the adults but were otherwise mostly black, with gray down layering their necks. Some birds stretched and flapped their wings, others preened, and, when a heavier rain fell, one raised its beak to the sky to drink. Snow squalls with giant flecks floated down at one point, driving hail or grabble at another, and in between, it mostly rained.

We had to land in two groups while the leaders stayed on shore. Mary and I stayed on the beach when the second group made the hike up to the birds, and we worked on the

Antarctic Fur Seals and ‘weaner’ Elephant Seal pups scattered about. The beach was mostly occupied by males staking territory, and periodically fights would break out. One feisty male was ripped in several places, and I tried some flash to bring out the blood. A few males were aggressive but gentle paddle pats on the whiskers kept the seals at bay.

We left the beach by 1:30 and returned to the boat by 2, soaked to the skin. Our gear was wet, our bags soaked, virtually everything was damp, and as I write this our room heater is blasting as we attempt to dry gear out before our 5PM next landing.

PM. We had a very short but very nice 1.5 hour or so landing at Jason Harbor, with a tiny bit of spitting snow occasionally dotting a lens’ front element. Elephant seal ‘weaners’ dotted the beach and grass tussocks, and on the hillside a few introduced Reindeer wandered by. Antarctic Fur Seals had the beach territories staked out but the seals were unaggressive, while along the beach a bull Elephant Seal patrolled, his bulbous nose and black eyes just barely about water line. The time was too short for the shooting, although the head cold I’d been fighting sapped my energy this afternoon and even lifting a partially filled backpack was exhausting.

Day 11, Fortuna Bay

Day 11, Fortuna Bay

Fortuna Bay is a beautiful beach where, minutes after landing, I spotted a Light-Mantled Sooty Albatross nesting on a cliff right above our landing site. These birds often nest among the tussocks on the cliff edges, and this bird was tucked in well, giving us only a beach-level view as, from above, the intervening grasses would have blocked it.

Fur Seals were active. One male, still sleek black and glistening from just emerging from the sea, ran a gauntlet of several seals until it settled at a location too close to two other males. Each in turn attacked, and at one point the new seal was turned on his side while his attacker bit his flank. He rolled upright and took the offensive and drove that seal back. Seconds later, he fought the other, and a few minutes later the first seal once again. Eventually he won his ground, with fresh, bright blood dripping from several wounds, around his neck, down his shoulder, across his back in several torn patches.

I worked on some wide-angle 14mm shots on Elephant Seals, using a monopod that I extended over my leg to create a fulcrum by which I could raise or lower the camera. Because of the changing light I tried Aperture Priority for some of the shots, and most worked, but on occasion too much shadow in a key area produced over-exposures that I hope will be recoverable in RAW.

There is a large receding glacier that flows into a broad valley dotted with King Penguins and seals. Several of our participants eventually worked their way there, an easy mile or more from our landing site, when a Katabatic Wind, the hurricane-force cold winds that South Georgia are famous for, rolled down unexpectedly. We got the call to evacuate the beach, a call that I missed on my radio, whose volume inexplicably had turned too low for me to hear. Jeff, one of the leaders, alerted me while he continued on to retrieve those at the glacier.

There is a large receding glacier that flows into a broad valley dotted with King Penguins and seals. Several of our participants eventually worked their way there, an easy mile or more from our landing site, when a Katabatic Wind, the hurricane-force cold winds that South Georgia are famous for, rolled down unexpectedly. We got the call to evacuate the beach, a call that I missed on my radio, whose volume inexplicably had turned too low for me to hear. Jeff, one of the leaders, alerted me while he continued on to retrieve those at the glacier.

That retrieval proved frustrating for Jeff, as the photographers he was herding were like cats, and as he moved to find new photographers to hustle to the beach those he left stopped and started photographing once again. Doing so, a speedy evacuation was slower considerably, and with consequences. By the time I reached the beach the wind was howling, and as I approached our landing site the beach was masked penguin-high in scouring sand, blasting across in a blackish veil. The surf was spraying, and while the incoming waves were not bad the route to the ship was almost obscured by salt spray.

We got everyone off the beach, watching the zodiacs bouncing across the seas. More worrisome were the zodiacs returning to the beach, manned by one sailor, which gave little weight or ballast to the raft. Our zodiac was the last, and as loaded and prepared to shove off the outboard motor failed, and we sat there, holding a bobbing zodiac against the wind and sand-blast. We called in a new zodiac that zipped in, bouncing across the waves and fighting air. Several zodiacs, as they had returned to shore for more passengers, had been airborne at times, their hulls completely off the water. Under those conditions an unusual gust can catch a zodiac and flip it, and that’s exactly what happened to our new zodiac. I missed the toss, as I intent on holding down the zodiac and keeping my face averted to avoid the blasting sand, but at the shouts I looked up to see the sailor hanging on to his overturned craft. Luckily he was close enough shore that the wind and rain continued to move him towards the shoreline, and after several tries of tossing a rope one of the sailors hauled him in. It took six people several tries until they righted the zodiac again, afterwards a third zodiac, that had come to the aid of the overturned zodiac, returned for us and returned us to the ship. It was a wet ride, and John, sitting across from me and facing the wind, was a comical sight as it looked as if someone was periodically tossing buckets of water into his face, the product of the blowing wind.

We got everyone off the beach, watching the zodiacs bouncing across the seas. More worrisome were the zodiacs returning to the beach, manned by one sailor, which gave little weight or ballast to the raft. Our zodiac was the last, and as loaded and prepared to shove off the outboard motor failed, and we sat there, holding a bobbing zodiac against the wind and sand-blast. We called in a new zodiac that zipped in, bouncing across the waves and fighting air. Several zodiacs, as they had returned to shore for more passengers, had been airborne at times, their hulls completely off the water. Under those conditions an unusual gust can catch a zodiac and flip it, and that’s exactly what happened to our new zodiac. I missed the toss, as I intent on holding down the zodiac and keeping my face averted to avoid the blasting sand, but at the shouts I looked up to see the sailor hanging on to his overturned craft. Luckily he was close enough shore that the wind and rain continued to move him towards the shoreline, and after several tries of tossing a rope one of the sailors hauled him in. It took six people several tries until they righted the zodiac again, afterwards a third zodiac, that had come to the aid of the overturned zodiac, returned for us and returned us to the ship. It was a wet ride, and John, sitting across from me and facing the wind, was a comical sight as it looked as if someone was periodically tossing buckets of water into his face, the product of the blowing wind.

PM. Grytviken.

A customs officer boarded our boat to clear us for landing, and this meaningless exercise delayed our departure by about an hour. The winds were calm and the air cool, and the sky filled with puffy clouds against a canopy of blue, perfect conditions for a visit to what is now the only occupied area of South Georgia.

Over the years, for safety reasons the vast industrial complex of the whaling station has been whittled away as it has been sanitized, removing tin that might blow free in high winds, and asbestos that one might inhale. The result is a small complex of rusting shells which hint at the larger story of what once transpired here.

I went immediately to Ernst Shackleton’s gravesite where I was anxious to try a 14mm WA shot of the cemetery and environs. Several cooperative Elephant seals dotted the trail, where I used a remote to attempt some animal in habitat shots. At 6, or so, as participants kept meandering in long after the appointed time, Chris, who was now sufficiently recovered from his seal bite to make the walk, gave a short talk in preparation to a toast to ‘The Boss.’ Kendrick, one of the pax, brought his own bottle of Irish Whiskey and Mary and I and a few others knocked down a shot at the conclusion of the toast.

I went immediately to Ernst Shackleton’s gravesite where I was anxious to try a 14mm WA shot of the cemetery and environs. Several cooperative Elephant seals dotted the trail, where I used a remote to attempt some animal in habitat shots. At 6, or so, as participants kept meandering in long after the appointed time, Chris, who was now sufficiently recovered from his seal bite to make the walk, gave a short talk in preparation to a toast to ‘The Boss.’ Kendrick, one of the pax, brought his own bottle of Irish Whiskey and Mary and I and a few others knocked down a shot at the conclusion of the toast.

That evening, on deck, the crew hosted an alcedo barbeque, with sausage sandwiches followed by beef, lamb, chicken, blood sausage, and another mystery meat to top off a complete day that provided a lot of memories, experiences, and, hopefully, expedition lessons.

Day 12, St. Andrews Bay.

Day 12, St. Andrews Bay.

We awoke at 5 for a 6AM departure to Saint Andrews Bay, one of the magical locations in South Georgia and, perhaps, the world. High Katabatic winds rolled off the large glacial face, chopping the sea in froth. Our landing was delayed until 9.

The weather held and we landed at 9, with clear skies over the seas and a shroud of clouds hanging over the mountains and shading the beach. We started by attempting a grand landscape, but the contrast difference was discouraging and after a half hour we released everyone to shoot where they wished. Through the day everyone ended up everywhere, moving up the slope for looking down shots upon the huge colony, or downriver looking up to the colony.

I spent most of my time on the beach, hoping to capture King Penguins as they surfed and scrambled ashore, but the beach was slow. Elephant Seals, however, were still breeding, and we had many examples of big bulls slogging along, caterpillar-like, chasing away rivals or literally engulfing a tiny female in a mating embrace. We had some question as to exactly how Elephant Seals mate, but those questions were answered through the day. The female’s vagina is, as one might expect, located right between the two rear flippers. The male’s penis, however, is located a short distance below the naval, and is usually retracted and invisible. The only sign, usually, is a double pucker mark, one for the naval and one for the penis. When a male attempts to mate he may bite the female’s neck (many females we saw had bloody necks) and wrap a fore-flipper around her body, in what can look like an affectionate embrace. Eventually, with much squirming, he positions his hindquarters such that his penile opening is directly behind her flippers, and insertion occurs, generally invisible to prying eyes. Sometimes, after mating, there was a few minutes when the male’s penis was still visible, a pink, flattish organ, and, presumably because of the rarity of the sighting, this was always noteworthy and a big hit.

Most of the fighting is finished, with the bulls now established in their hierarchies, but it was interesting to see this order as what might appear to be a dominant bull ‘bully’ lesser seals, but give way, in haste, when the true king of the beach appeared. One bull I was sitting near seemed oblivious to everything, and powerful, but finally another bull came out of the surf and, after a brief tussle where the two raised themselves high, ‘my’ bull retreated to the surf. The victor displayed several times, rearing high so that his flippers cleared the sand, before settling down to sleep.

Most of the fighting is finished, with the bulls now established in their hierarchies, but it was interesting to see this order as what might appear to be a dominant bull ‘bully’ lesser seals, but give way, in haste, when the true king of the beach appeared. One bull I was sitting near seemed oblivious to everything, and powerful, but finally another bull came out of the surf and, after a brief tussle where the two raised themselves high, ‘my’ bull retreated to the surf. The victor displayed several times, rearing high so that his flippers cleared the sand, before settling down to sleep.

Big bulls blast their challenging roar, doing so several times as their nasal pouch inflates and ripples with the intensity of their open-mouthed, steam-spewing vocalizations.  Dominant males would sometimes call in repetitive snorting roars for a minute or more, with their huge sides undulating from the force of the effort. When lesser males came near to a harem master and his cows the dominant bull would roar and, like a sandworm from Dune, undulate across the sand, over cows and calves, charging at the intruder who would immediately retreat. All of the bulls still had open scars, so the fierceness of the fighting just a few weeks earlier would have been something to see.

Dominant males would sometimes call in repetitive snorting roars for a minute or more, with their huge sides undulating from the force of the effort. When lesser males came near to a harem master and his cows the dominant bull would roar and, like a sandworm from Dune, undulate across the sand, over cows and calves, charging at the intruder who would immediately retreat. All of the bulls still had open scars, so the fierceness of the fighting just a few weeks earlier would have been something to see.

Despite all this about seals, St. Andrew’s true spectacle are the King Penguins, perhaps 1.5 million’s worth, that line the beach, moult in small groups, cluster together as brown, fuzzy chicks, or tend to the young in the colony that extends for over a thousand yards. Walking towards the colony I went from the relative wind-swept silence of the beach, and the occasional blasts of a honking seal, to the near continuous cacophony of trumpeting King Penguins, a screechy, piping call that resounded across the colony. Brown coated chicks peep or whistle, and the incredible thing of all this is that adult and young locate one another by voice recognition. Mary saw one chick run about 25 meters through the colony when it heard its parent, as the chick ululated as it ran through and over its mates.

We stayed on the beach until 7, with the last enthusiastic passengers squeezing out every moment despite the fact that the light had dimmed to a dullness by 6, and the dampness and penetrating cold settled in. It was a hard day on gear, with one person tripping and breaking a 400mm DO lens, another dousing a camera, another person falling backwards and soaking their backpack, but hopefully without ruining their gear, and still another person breaking a tripod.

We stayed on the beach until 7, with the last enthusiastic passengers squeezing out every moment despite the fact that the light had dimmed to a dullness by 6, and the dampness and penetrating cold settled in. It was a hard day on gear, with one person tripping and breaking a 400mm DO lens, another dousing a camera, another person falling backwards and soaking their backpack, but hopefully without ruining their gear, and still another person breaking a tripod.

I’ll remember most that hour or so when the sun broke through the clouds, bathing both the beach and the rugged, cloud-capped mountains in brilliant sunlight, and glowing penguin breasts shining in the light. If we get weathered out our next two days, and that’s always a possibility, South Georgia ended up still being very good to us.

Day 13

Day 13

AM. Royal Bay and Ross Glacier.

After a leisurely breakfast after yesterday’s hard day we did several zodiac rides along the glacial face of Ross Glacier. The sky was relatively clear and the day sunny, and with little or no wind the conditions were perfect. Antarctic Terns hovered and dove along the open sea edge fronting the glacier, and, amidst the sea brash ice, Snow Petrels sat on tiny blocks of ice and permitted very close approaches. Two of the zodiac drivers took their passengers fairly close to the ice face, but my zodiac wisely kept its distance. In Alaska, this summer, we saw a virtual sky scraper of ice blast from beneath the sea and suddenly surface unexpectedly, amidst a cascade of icy water. Another series of faces broke, creating a virtual tidal wave of water propelled from the displaced ice. Those two experiences, and a close-call two years ago on our Antarctic trip, has made me conservative, and safe.

PM. Cooper’s Bay.

Although Macaroni Penguins are an abundant species, their nesting colonies are often inaccessible, and I’ve only visited one, here at Cooper’s Bay, where we landed and walked among the thick tussock grasses. Most times we zodiac around the colony edges, which we did this afternoon. Apparently the nesting season had just begun as the usual number of birds were missing. Still, small groups of penguins moved about the rocks, and there were enough to provide some shooting. However, there was a bonus.

Although Macaroni Penguins are an abundant species, their nesting colonies are often inaccessible, and I’ve only visited one, here at Cooper’s Bay, where we landed and walked among the thick tussock grasses. Most times we zodiac around the colony edges, which we did this afternoon. Apparently the nesting season had just begun as the usual number of birds were missing. Still, small groups of penguins moved about the rocks, and there were enough to provide some shooting. However, there was a bonus.

An adult Leopard Seal cruised the periphery of the colony, hunting for macaroni penguins. Leopard Seals are the ultimate predator of the coast, large, up to 12 feet or more, serpentine or dragon-like, with a head like a marine dinosaur and a mouth shaped with a slight smile that, when opened, reveals rows of peg-like teeth. The seal was curious and repeatedly visited our zodiacs, and during the second round of zodiac rides the seal killed and ate two penguins. Some participants had luck with getting some shots as the seal carried its kill, but more often Giant Petrels, mobbing the kill site like vultures at a kill, blocked any good shots.

Day 14, Drygalski Fjord

Day 14, Drygalski Fjord

A wind kicked up to near hurricane force with a storm sweeping past South Georgia. We were scheduled to cruise up the fjord for landscapes and snow petrels, but the force of the wind kept us at the mouth of the fjord for most of the day. Clouds shrouded the peaks and the incessant waves were flattened, their tops skimmed off by the blasting force of the wind. It was a memorable visual, and I risked the wind for a few minutes to catch a landscape/wave image that I hope would tell the story. Toward the end of the day our captain sailed up the fjord to its end, giving the passengers some idea of the depth and scale of the area, although with the wind now sandwiched between the two sides of the canyon it was almost impossible to be on deck to photograph.

Day 15, At Sea

Day 15, At Sea

The sea was still fairly choppy and tumultuous from the passed storm, but a few photographers weathered it out to photograph the flocks of Cape Petrels, Giant Petrels, Snow Petrels, and the occasional Albatross the glided by.

Most of the day was spent fairly quietly, with a few lectures and a lot of downloading and editing.

Day 16, At Sea

The seas calmed down and Southern Fulmars and Antarctic Petrels, near look-alikes of the abundant Cape Petrel but with a long white band extending through their wing secondary feathers, patrolled close to the boat nearly all morning. Lectures kept the leaders busy, and by the time I was free to shoot the birds seemed to have disappeared. Disappointed, Mary and I took our showers early and now, warm and clean, returned to the lounge to now see a flock of 20 or 30 Antarctic Petrels keeping pace with the ship just yards away. We let them go.

After dinner, however, we had good evening light and the petrels returned and most of us headed back out on deck to fight the wind for the very cooperative Antarctic Petrels. They flew towards the sun and their forequarters were bathed in a soft golden light, making for the best shots of the day for these birds and, for us, making up for the opportunities we had passed on earlier.

After dinner, however, we had good evening light and the petrels returned and most of us headed back out on deck to fight the wind for the very cooperative Antarctic Petrels. They flew towards the sun and their forequarters were bathed in a soft golden light, making for the best shots of the day for these birds and, for us, making up for the opportunities we had passed on earlier.

That evening several photographers, and all of the Mexican photographers, participated in a ‘South Georgia Photo Contest’ where, in 9 categories, participants were allowed to enter 1 image in 5 of the 9 categories. Winners were determined by a show of hands among the 50 some attending, and as it turned out no photographer won more than 1 category. Mary won in the action category with a great shot of an elephant seal bull, with waves smashing in a white froth around it in the surf. I had a second, which counted for nothing, in the people category where I entered a Black n White conversion of Ernst Shackleton’s grave. I was beaten by a shot of an elephant seal’s eye with the reflection of photographers inside. The show was a real hit, and we hope that the Mexican organizers will reopen the Falkland Island contest, which was done only among their group. It’d be interesting to see a broader portfolio there!

Day 17, Antarctic Sound

Day 17, Antarctic Sound

We arrived at the peninsula a day earlier than expected, which meant that our booked and scheduled landings were still one day away. Nonetheless we found a landing location that was open but as Joe and Monica headed to the beach to scout a landing the wind kicked up, producing swells that, at the ship landing where people board the zodiacs, the water line fluctuated by 5 very dangerous feet. The shore scouting went no better, as the snow had piled into steep mushroom-like cliffs almost to the beach edge, leaving no room for penguins and people, and no where to go had everyone gone ashore. The tide was falling, too, and the water conditions treacherous, and that plan was abandoned.

We spent the rest of the morning cruising through the Sound, passing icebergs, glacial landscapes, and our first Adelie Penguins perched on small growler iceberger bits we passed.

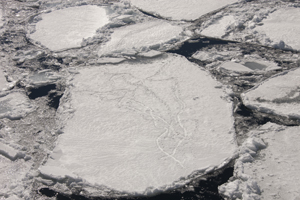

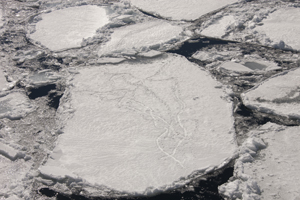

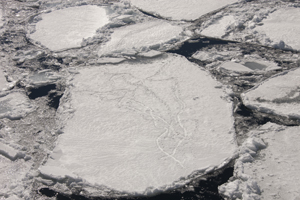

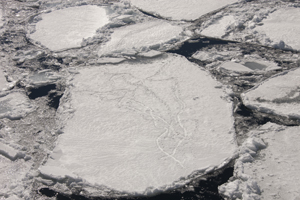

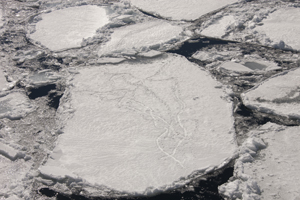

PM. We zodiac rode through a landscape of pancake ice through the late afternoon, after spending the earlier part of the day cruising towards a new landing site. That site was, however, inaccessible due to the pancake ice that accumulated at depth far from shore. From our ship the island looked devoid of penguins, but they may have been too high on the slopes or, as likely, unable to reach the rookery because of the jammed up ice.

Still, the zodiac cruising was a real success, and we motored very close to a very oblivious Crab-eater Seal that, at its best, would occasionally rear its head up to look curiously around. The light was great, and with a polarizer the ice and sea were wonderful.

Day 18, Paulett Island

Paulett Island hosts a huge Adelie Penguin rookery that was fully occupied, with birds sweeping up the slopes for hundreds of yards. A beautiful arched iceberg drifted offshore, and shortly after landing several of us boarded zodiacs again to motor about the ‘berg, getting various angles and, for those lucky enough, Adelie Penguins in the foreground. Occasionally a small flock would hop into the sea but almost immediately turn around and torpedo back onto the ice floe. The first time this happened no one was ready but on subsequent occasions we shot several , and hopefully one of those times I was lucky.

Paulett Island hosts a huge Adelie Penguin rookery that was fully occupied, with birds sweeping up the slopes for hundreds of yards. A beautiful arched iceberg drifted offshore, and shortly after landing several of us boarded zodiacs again to motor about the ‘berg, getting various angles and, for those lucky enough, Adelie Penguins in the foreground. Occasionally a small flock would hop into the sea but almost immediately turn around and torpedo back onto the ice floe. The first time this happened no one was ready but on subsequent occasions we shot several , and hopefully one of those times I was lucky.

I spent little time ashore, spending the majority of my time aboard a zodiac, but during that short time I had a nice pair of Kelp Gulls and some cooperative Snowy Sheathbills on an ice flow. After lunch, we motored passed and then circled another iceberg with an arch, which, from the boat, gave an entirely different perspective.

I spent little time ashore, spending the majority of my time aboard a zodiac, but during that short time I had a nice pair of Kelp Gulls and some cooperative Snowy Sheathbills on an ice flow. After lunch, we motored passed and then circled another iceberg with an arch, which, from the boat, gave an entirely different perspective.

PM. Brown’s Bluff

By 5 we reached our second destination of the day, Brown’s Bluff, which marked our first official landing on the continent of Antarctica. Brown’s Bluff has a large colony of Adelie Penguins, and most of us frustrated ourselves attempting to get shots as penguins rocked out of the water, sometimes rising four feet or more into the air before landing on an ice floe. A leopard seal was spotted cruising amongst the ice but the seal never attacked a penguin. Later, it hauled up onto a floe and most zodiacs had a close pass-by, but few got photos as it was late and we were behind schedule. By 7 we were off the island and, after dinner, we started our 13 hour cruise to head deeper south along the peninsula.

By 5 we reached our second destination of the day, Brown’s Bluff, which marked our first official landing on the continent of Antarctica. Brown’s Bluff has a large colony of Adelie Penguins, and most of us frustrated ourselves attempting to get shots as penguins rocked out of the water, sometimes rising four feet or more into the air before landing on an ice floe. A leopard seal was spotted cruising amongst the ice but the seal never attacked a penguin. Later, it hauled up onto a floe and most zodiacs had a close pass-by, but few got photos as it was late and we were behind schedule. By 7 we were off the island and, after dinner, we started our 13 hour cruise to head deeper south along the peninsula.

One of our participants was using a Monopod GM5561T with RRS monopod head instead of a tripod. He loved it, and when I tried out the monopod I found it extremely convenient and flexible and, with the shorter lenses and the ISO that we were using, the stability was more than adequate. In the future, I’ll probably only carry a monopod for these trips for the speed and ease of setup. The only negative I see in this system is if another camera is in play, where, when a camera is on a tripod, the setup can remain in place while the other camera is in use. With a monopod the unused camera, and monopod, will have to be laid down, set on a pack or rock. This is not a big negative for The South, however, because an unexpected katabatic wind could crash an unattended tripod/camera to the ground, sand, or surf, and this isn’t unusual. Both Mary and I have had our cameras knocked to the ground by these winds, so having the unused camera lying down might be a real advantage.

One of our participants was using a Monopod GM5561T with RRS monopod head instead of a tripod. He loved it, and when I tried out the monopod I found it extremely convenient and flexible and, with the shorter lenses and the ISO that we were using, the stability was more than adequate. In the future, I’ll probably only carry a monopod for these trips for the speed and ease of setup. The only negative I see in this system is if another camera is in play, where, when a camera is on a tripod, the setup can remain in place while the other camera is in use. With a monopod the unused camera, and monopod, will have to be laid down, set on a pack or rock. This is not a big negative for The South, however, because an unexpected katabatic wind could crash an unattended tripod/camera to the ground, sand, or surf, and this isn’t unusual. Both Mary and I have had our cameras knocked to the ground by these winds, so having the unused camera lying down might be a real advantage.

One of our participants was using a Monopod GM5561T with RRS monopod head instead of a tripod. He loved it, and when I tried out the monopod I found it extremely convenient and flexible and, with the shorter lenses and the ISO that we were using, the stability was more than adequate. In the future, I’ll probably only carry a monopod for these trips for the speed and ease of setup. The only negative I see in this system is if another camera is in play, where, when a camera is on a tripod, the setup can remain in place while the other camera is in use. With a monopod the unused camera, and monopod, will have to be laid down, set on a pack or rock. This is not a big negative for The South, however, because an unexpected katabatic wind could crash an unattended tripod/camera to the ground, sand, or surf, and this isn’t unusual. Both Mary and I have had our cameras knocked to the ground by these winds, so having the unused camera lying down might be a real advantage.

Day 19, AM Hydrurga Rocks

We arrived at Hydrurga Rocks shortly before 10AM, riding our zodiacs into a tiny sheltered bay where we landed. In the high country nearby there are several different small colonies of Chin-strap Penguins, and although the snow was deep it was surprisingly hard packed and fairly easy to walk across. On occasion someone would posthole deep, sinking up to a knee or deeper, but the trail, broken by hundreds of footsteps, grew fairly firm quickly.

We arrived at Hydrurga Rocks shortly before 10AM, riding our zodiacs into a tiny sheltered bay where we landed. In the high country nearby there are several different small colonies of Chin-strap Penguins, and although the snow was deep it was surprisingly hard packed and fairly easy to walk across. On occasion someone would posthole deep, sinking up to a knee or deeper, but the trail, broken by hundreds of footsteps, grew fairly firm quickly.

A thick canopy of gray clouds hung low, creating a reflective light that was surprisingly bright. The penguins, at the colony, were fairly unattractive, stained by feces or regurgitations to a krill-colored orange. Birds fresh from the sea were gleaming white, but those were few.

A thick canopy of gray clouds hung low, creating a reflective light that was surprisingly bright. The penguins, at the colony, were fairly unattractive, stained by feces or regurgitations to a krill-colored orange. Birds fresh from the sea were gleaming white, but those were few.

Seven Weddel’s Seals had hauled out on the snow a hundred yards or so from the beach. With the steep cliff-like overhang of snow I have no idea how one seal, let alone seven, found their way off of the beach nor why they’d continue to move uphill to their resting place. Several of us flopped down upon our bellies and slithered forward, providing a seal’s eye perspective that kept the seals relaxed and calm. Seals, even pretty ones like the Weddel’s, don’t do very much and the best we managed there were some shots as a seal awoke and scratched.

PM.

We landed at a Bay where a field of stranded icebergs lay and a large, scattered colony of Gentoo Penguins marked most of the lower hill crests. Almost immediately after landing several zodiacs went back out for iceberg tours, but Mary and I stayed ashore, hoping to film porpoising penguins and birds atop the ice floes. We were not too successful at this.

We landed at a Bay where a field of stranded icebergs lay and a large, scattered colony of Gentoo Penguins marked most of the lower hill crests. Almost immediately after landing several zodiacs went back out for iceberg tours, but Mary and I stayed ashore, hoping to film porpoising penguins and birds atop the ice floes. We were not too successful at this.

The zodiac cruises went well with everyone feeling as if they’d been transported to another world, which in a way they were, and from the zodiac shooters had, perhaps, the best view of the Gentoo colonies. Gentoos, like many penguins, nest high, and although the effort seems meaningless the behavior might have two explanations.

On the higher ridges snow clears quickest, blown by the wind, and thus nest sites, and nests with snow-free eggs are safest. There may also be a degree of sexual selection going on, with the fittest, strongest birds of both sexes making the steep uphill climbs, demonstrating fitness. Perhaps, for the penguins, the upward journey might be analogous to beauty with people, as physical beauty and attraction, with people, may be mirrored in the penguins by a demonstration of strength, as the best birds make the longest climbs. It is a thought.

On the higher ridges snow clears quickest, blown by the wind, and thus nest sites, and nests with snow-free eggs are safest. There may also be a degree of sexual selection going on, with the fittest, strongest birds of both sexes making the steep uphill climbs, demonstrating fitness. Perhaps, for the penguins, the upward journey might be analogous to beauty with people, as physical beauty and attraction, with people, may be mirrored in the penguins by a demonstration of strength, as the best birds make the longest climbs. It is a thought.

We returned to the ship for our second barbeque and open bar/party, which for some was followed by a big, late, birthday party celebrated by two crew members. Some folks partied until 2, while others awoke by 2 to check for a hoped for sunrise painting the mountain ridges in alpen glow. In the evening low clouds shrouded the mountain tops and, near 11PM, Mary and I hoped for late light, and although the clouds and glaciers glowed a faint pink for a few seconds, nothing worthwhile materialized and we went to bed, hoping for a 2AM sunrise that never came.

Day 20, Gerlache Strait and Lemaire Channel

Day 20, Gerlache Strait and Lemaire Channel

Our plan was to cruise down through the Lemaire channel which, at its narrowest, would be shorter than the length of our boat. As we approached an icefield appeared, and as we neared it became obvious that the channel was too ice-choked by floes, pancake ice, and ice bergs pushed into a jumbled mass by a northern wind. Our captain pushed in a short distance to give everyone a feel for the event, and perhaps its futility, as we bumped loudly into a hidden block of ice. We turned around and headed north, to Paradise Bay for more zodiac cruising.

PM. Paradise Bay

We landed at Brown Station in Paradise Bay, a now abandoned Argentinean outpost on the peninsula. Several passengers climbed the steep, high ridge that overlooks Paradise Bay and the station, providing a stunning overlook of the Bay and a great place to slide down, feet first, for a fast downhill descent. Several people made the round trip five times, videoing the experience.

Mary and I spent our afternoon on two zodiac cruises, the first going to the front of a large glacier that ended in the bay, and the second chasing Minke Whales, circling a cooperative Crab-eater Seal, and shooting blue ice. Joe Van Os’s zodiac encountered an extremely feisty Leopard Seal that they stayed with for a full 1.5 hours. The seal ‘attacked’ the zodiac at least twenty times, swimming in at speed and surfacing near, attempting to create a bow wave that would capsize the craft. Four times or more the seal zoomed underneath the zodiac, mouth agape and bubbles spewing, a sure sign of aggression. The seal would often leap up to an ice ledge, then slide back in, and in all, providing a huge amount of shooting opportunities.

Mary and I spent our afternoon on two zodiac cruises, the first going to the front of a large glacier that ended in the bay, and the second chasing Minke Whales, circling a cooperative Crab-eater Seal, and shooting blue ice. Joe Van Os’s zodiac encountered an extremely feisty Leopard Seal that they stayed with for a full 1.5 hours. The seal ‘attacked’ the zodiac at least twenty times, swimming in at speed and surfacing near, attempting to create a bow wave that would capsize the craft. Four times or more the seal zoomed underneath the zodiac, mouth agape and bubbles spewing, a sure sign of aggression. The seal would often leap up to an ice ledge, then slide back in, and in all, providing a huge amount of shooting opportunities.

Day 21, Half Moon Bay

Our last morning was a short but beautiful landing at one of the most picturesque locations along the peninsula, Half Moon Bay. We arrived by 10AM and, because of the impending storm forecasted for the Drake Passage, we had to be off again by noon.

Our last morning was a short but beautiful landing at one of the most picturesque locations along the peninsula, Half Moon Bay. We arrived by 10AM and, because of the impending storm forecasted for the Drake Passage, we had to be off again by noon.

Half Moon Bay hosts a large colony of Chin-strap Penguins nestled amongst the ledges and rocky spires. The exposed rocks are coated by brilliant orange lichens, and Chris Edwards photographed an endemic large Mite that feeds upon this primitive plant. Kelp Gulls nest in a small colony on one of the outcrops, and Skuas patrol the skies, watching for unguarded penguin eggs.

The landscape possibilities on Half Moon Bay are among the best, with one direction overlooking a large bay and sweep of glaciers, and, almost directly opposite, another view offering a great vantage for watching a penguin highway as birds trudge upslope to their nests, framed by a brilliant orange cliff face and a distant row of mountains.

The penguins were still on eggs, and typical for a colony the birds on nests were mostly stained and colored by a krill-pink wash. Birds fresh from the sea, however, sparkled clean and bright, and in small groups or alone they waddled past our cameras to their nests.

We departed on time and began our journey north, cutting out a planned afternoon visit to Deception Island, in still pleasant seas, with a small swell and, with little wind, a birdless sky. As the day progressed seabirds rejoined us, with large flocks of Antarctic Petrels, a few Southern Fulmars, and the ever-present Pentado cruising along our boat. On the open sea we had a great sunset, and several of us tried framing flying Pentados against the sky, illuminating their otherwise silhouetted shapes with flash. With mixed results.

Day 22, At Sea

With a huge Drake storm ahead of us we continued north, traveling across surprisingly calm seas through the morning and early afternoon. Several Light-mantled Sooty Albatrosses flew apace with the ship, and those that were out shot some great shots, frame-fillers, of this often elusive seabird.

By 3 the seas began to rise, and within an hour or so we were in the storm, with waves and swells averaging 3 to 4 meters, with a few rough seas rocking the ship with 6 meter waves. Those capable went up to the bridge to watch the excitement, shooting stills and videos as periodic waves smashed over the brow, creating a huge splash that smashed against the bridge windows four decks above the sea. The storm continued throughout the evening, although nearly everyone made dinner, but as the seas grew even rougher and the seas higher the excitement began to morph into an exercise in tolerance and tedium. We went to bed drugged heavily for seasickness, rocking about, and awakened at one point when a big wave knocked our desk drawer clear across the room.

Day 23, Beagle Channel

We arrived at the entrance to the Beagle Channel sometime during the night, awakening to rain and 50 knot winds. Fortunately, sheltered by the surrounding land the ship was almost motionless, and we spent the day anchored, now only 5 official hours from docking. Unfortunately, our docking time and our hotels or flights are all booked for the following day, but on the extremely positive side we avoided the brunt of the storm, and now, under calm seas, everyone has time to pack luggage in a stress free environment. In the afternoon we did another photo contest, this time on the Antarctic portion of the expedition.

Day 24, Ushuaia

We docked, said our goodbyes, and departed the ship, with the group splitting up for various flights during the day and some, like Mary and I, overnighting in Ushuaia.

Day 25, Ushuaia to home

We left on an afternoon flight for Buenos Aires, expecting to have an easy 4 hour layover before our flight to Atlanta and on to home. Unfortunately, our scheduled flight to the international airport was changed, en route, to the domestic airport where, after an hour of circling, we finally landed. No one there could give us information, but eventually we were told that a bus would be coming ‘in 5 minutes’ to take us across town to the international airport. After 50 minutes and now barely 1.5 hours from the cut-off for a check-in we took a taxi, weaving through the city at speed to finally arrive at the airport 50 minutes later. We checked in, and then endured incredible inefficiency at the airport custom’s and security areas, and we didn’t board our plane until it was technically 5 minutes from departure. 6 people also stranded at the domestic airport did take the bus, and fortunately the airline did wait and hold the plane so that everyone made the flight. Nonetheless we were glad we had taken the taxi to avoid the stress, as one of the trip’s pax took the bus and was convinced he’d miss his flight. He did not.

Otherwise, the rest of the trip went well, with Mary and I finally arriving home at 5PM of Day 26.

Antarctic 2011

The Falklands, South Georgia,

and the Antarctic Peninsula

Trip Report

For the fourth time in eight years, Mary and I joined Joseph Van Os Photo Safaris as part of the photo leader team for a lengthy photo expedition to three of the most spectacular wildlife and landscape locations in the Southern Hemisphere. This year’s trip to the great South was characterized by real adventure, experiences we’d not had in any of our three previous trips to the southern seas. These highlights included a zodiac flipped over by high winds, with, fortunately, only the boat sailor aboard and whom was rescued; an attack by an Antarctic Fur Seal that I stopped by shoving my tripod-mounted camera in its face (the same seal later bit one of our other trip leaders); and a turbulent cruise through the Drake Passage in near hurricane-force waves.

We’d hoped for snowy landscapes, starting the trip at least a week earlier than any previous trip we’d made, but almost all of our precipitation was rain, which bodes unsettlingly for a global climate change or warming. Still, experiences and photographs were varied and spectacular, and included Antarctic Fur Seals that crowded many of the beaches of South Georgia; Elephant Seals that were finishing up most of their mating activity; and penguins that were busy laying eggs and/or incubating. One of our zodiacs had an incredible experience with the South’s ultimate predator, a Leopard Seal, that actually punctured one of the air compartments of that zodiac as it played with, or attacked, the zodiac, providing some excitement in addition to some stunning photo opportunities.

The following is the day-by-day account of the trip, providing a bit more depth to the experience. Enjoy.

Day 1 – 2.

Travel days, with an arrival into Ushia, the southernmost city in the world where one of our four pieces of luggage did not arrive with us. Fortunately our luggage, and that of two other participants of the trip, arrived and our boarding of the boat proceeded uneventfully. That evening, and the following day we cruised almost lake-like waters, making incredible time as we headed toward New Island, one of the westernmost islands in the Falkland Island archipelago.

Day 3. New Island.

Day 3. New Island.

We arrived around midnight, anchored, and awoke to partly cloudy skies, no wind, and fairly warm temperatures. New Island has a large Gentoo colony improbably located along one of the highest points of the grassy hillsides, several hundred feet above the water. The main attraction, however, is the large Black-browed Albatross and Rock-hopper Penguin colony located on the opposite side of the isthmus where we anchored. Nearly everyone, despite age or weight, made the mile long walk to the colonies, which began, intimidatingly enough, with a steep  70 foot embankment. Once over that crest the rest of the hike is a fairly easy uphill trek along an old jeep trail. En route, Striated Caracaras flew down to investigate and, later, flew in to snatch as many as twenty Upland Goose chicks, sometimes wiping out an entire clutch.

70 foot embankment. Once over that crest the rest of the hike is a fairly easy uphill trek along an old jeep trail. En route, Striated Caracaras flew down to investigate and, later, flew in to snatch as many as twenty Upland Goose chicks, sometimes wiping out an entire clutch.

None of the nesting birds had chicks, and not all had eggs, and patient Albatrosses sat quietly on their mounded nest, awaiting mates or the arrival of an egg. Occasionally a caracara would hop in, trying to steal an egg, and occasionally being successful. Peale’s Dolphins plied the waters far below, their black and white pattern resembling a miniature orca, and King Cormorants periodically flew in, carrying nesting material for their nests, located in a deep crevice.

The day started cool and partly cloudy but by day’s end the skies were cloudless and the afternoon was warm. A slight breeze picked up, giving lift for albatrosses that, earlier in the day, sat virtually motionless on their nest mounds. To arrive at a colony of albatrosses, and seeing none in flight, is a bit deflating, and boring, as their glides across the sky and landscape give incredible energy to the scene. By the end of the day, however, some birds were flying, and Mary and I and John challenged ourselves, capturing white birds against the backdrop of coal black cliffs. The group headed back some time after 5, with our last departure from a still calm beach by 6:30, with plenty of happy but very tired photographers.

The day started cool and partly cloudy but by day’s end the skies were cloudless and the afternoon was warm. A slight breeze picked up, giving lift for albatrosses that, earlier in the day, sat virtually motionless on their nest mounds. To arrive at a colony of albatrosses, and seeing none in flight, is a bit deflating, and boring, as their glides across the sky and landscape give incredible energy to the scene. By the end of the day, however, some birds were flying, and Mary and I and John challenged ourselves, capturing white birds against the backdrop of coal black cliffs. The group headed back some time after 5, with our last departure from a still calm beach by 6:30, with plenty of happy but very tired photographers.

Day 4, AM. West Point Island

Day 4, AM. West Point Island

We arrived on WPI by 8:30 under incredibly blue skies and a calm wind. WPI features a ‘settlement,’ what was once a sheep farm and is now a homestead with limited sheep and cattle raising and a catering to tourists, where songbirds, caracaras, and geese cluster close by. A very long walk away there is a Black-browed Albatross and Rock-hopper Penguin colony and, after we unloaded everyone, I hitched a ride with the land care-taker and with several others headed across the moorland to the colony. En route we passed several participants that took the hike, which I avoided without shame with a bad back. The caretaker took me about, showing where to go and where not to, and I was stunned by the proximity of the birds – albatrosses where perched literally beside the trail. He also pointed out a peninsula-like spit of land where he said some photographers go, via a circuitous route that skirted the colony but that required negotiating a narrow spine of land where, on either side, steep cliffs dropped to the sea. With some reluctance I had planned on taking some of the more enthusiastic shooters there, but as I scouted it out later I noticed the albatrosses were nesting all along the spine, making it almost impossible to travel without disturbing the birds. Consequently, I apologized and passed on this.

We spent a good part of the morning photographing albatrosses in flight, especially using slow shutter speeds where I panned. Mary worked on the beach the entire time, photographing flying Kelp Geese, Falkland Thrushes, Turkey Vultures, and more. I stayed at the colony, and as of now I haven’t looked at any image, but I imagine the keeper ratio will be small.

We spent a good part of the morning photographing albatrosses in flight, especially using slow shutter speeds where I panned. Mary worked on the beach the entire time, photographing flying Kelp Geese, Falkland Thrushes, Turkey Vultures, and more. I stayed at the colony, and as of now I haven’t looked at any image, but I imagine the keeper ratio will be small.

PM. Graves Beach.

The afternoon grew dreary and by the time we boarded the zodiacs it began to spit rain and, for a few minutes, spotty snow. By the time we reached the beach it was raining hard enough that none of the leaders bothered to pull out camera gear from the dry bags. Most of the participants did photograph, braving the rain as they shot the large Gentoo Penguin colony and the schools of penguins that surfed, dove, and jumped into the beach. Mary and I visited the beach where I ‘pretended’ to shoot, trying to anticipate where I’d have focused a big lens. I’m glad I didn’t, because even in practice I know I was not very successful. Nonetheless we stayed on the beach to 7, and by then the few of us left were cold and very damp. Ironically, when we returned to the boat I got a hot shower but the heating system quit as Mary took her’s, and after a cold day on the beach that was something she didn’t need.

Day 5. Saunders Island

Day 5. Saunders Island

Despite yesterday’s rains the sky was brilliant this morning with almost perfect conditions, warm and windless. Saunder’s features three great shooting opportunities, with perhaps the largest Gentoo Penguin colony in the world, a great haul-out beach and swimming pool for Rock-hopper Penguins, and on the cliffs above, very accessible and open rookeries and mixed colonies of King Cormorants, Black-browed Albatrosses, and Rock-hopper Penguins.

We arrived on the beaches and were ready to disperse by 9, and I took a few photographers up the slopes for the albatross colony. In the near windless conditions the birds, we suspect, were not flying, and so the Rock-hoppers waylaid us for hours, as they marched the several hundred feet from the surf to a little fresh water stream to drink. Large flocks of King Cormorants occasionally soared by, swirling and circling before dropping close by into their nests, mixed among the Rock-hopper Penguins. Many of the birds carried vegetation in their bills, much of it land-based plants and green, leafy algae.

As the morning progressed the winds increased and the albatrosses took flight, circling about to drop back into their nests, their webbed feet flared for breaking and, perhaps, steering. Skuas and Striated Caracaras patrolled the edges, with the skuas occasionally dropping into the colony to steal an unguarded egg.

The afternoon light was perfect for the Rock-hopper swimming pool and birds popping from the surf, their feathers glistening and pristine from the sea, where the birds in small groups hopped up onto the rocks and continued either to the pool or to climb the cliffs to their rookeries. Gentoos continued to amass along the sandy beach, with reflections stretching long across the mirror-like wet sands.

I ended the day with a very cooperative pair of Pied Oystercatchers and, in the last hour on shore, a visit with the owners of Saunders, the Pole-Evans, who we’ve known for years, since film days when we would often spend weeks on photo tours on three of the Falkland Islands.

The visit to Saunders concluded what has probably been our most successful trip to these islands since we started doing these cruises, and with the near perfect light all day I shot nearly over 60 gbs, which translated to almost 3,000 images for the day – there will be some long editing sessions ahead!

Day 6 and 7. At Sea

Day 6 and 7. At Sea

We left the Falklands and continued across the South Atlantic in a following sea, where a west wind helped propel us forward at about 13 knots. The winds, blowing from our backs, produced swells that went with us, so the boat was far more stable than had the winds been blowing from any other direction. We spent the days attending lectures, editing, and shooting birds from the deck. One of the passengers, on Day 7 and early, was out on the upper deck when a rogue wave hit the ship from the side, dousing her in sea water. Fortunately no one was on the lower deck, where the force of that wave could have caused injury or worse.

Unlike our other cruises, virtually no one is sick, and our meals are attended by everyone. We had our first Wandering Albatrosses on Day 6, and on Day 7 both a Light Mantled Sooty and a Gray-headed Albatross passed by. While there is still wind, oddly enough Day 7 was relatively light on birds, with the same two or three wandering albatrosses circling infrequently behind our ship. I never saw an albatross flap, for on stiff winds they soared down almost to water level, sometimes with the trailing edge of a wing streaking the surface, where the upward push of the wind propelled them up again into a high arch where, time and again, this see-saw glide would give them lift, aided by a constant wind. In deal calm and windless seas this required lift is absent, and the air is empty of birds. I’ve seen this on other trips and while the sailing is pleasant the days are long and dull.

Day 8, At Sea and to South Georgia, Landing at Right Whale Bay

Day 8, At Sea and to South Georgia, Landing at Right Whale Bay

The seas were relatively calm and shrouded in a thick fog, and our morning was spent in lectures, followed by a vacuuming session to remove any potential invasive seeds from our clothing and bags. The weather did not improve by the time we anchored in Right Whale Bay, but our landing, often a challenge on South Georgia, went remarkably smooth.

Despite the constant blowing drizzly mist we attempted some photographs, while many of the participants avidly shot away, despite the weather. A bull Elephant Seal rose its forequarters up high repeatedly, snarling its snoring honk with its inflated nasal flap, steam blasting from its maw like smoke from a dragon’s mouth. The beaches are covered with bull Antarctic Fur Seals, on territory and testy, chasing rivals and our participants. Most seal interactions are aggressive bluffs, with males coming together and bobbing and weaving heads, and neck-bumping like pro football players chest bumping after a play. Rarely seals would engage, biting each other’s necks and shaking vigorously.

Despite the constant blowing drizzly mist we attempted some photographs, while many of the participants avidly shot away, despite the weather. A bull Elephant Seal rose its forequarters up high repeatedly, snarling its snoring honk with its inflated nasal flap, steam blasting from its maw like smoke from a dragon’s mouth. The beaches are covered with bull Antarctic Fur Seals, on territory and testy, chasing rivals and our participants. Most seal interactions are aggressive bluffs, with males coming together and bobbing and weaving heads, and neck-bumping like pro football players chest bumping after a play. Rarely seals would engage, biting each other’s necks and shaking vigorously.

King Penguins massed along the beach and huddled in large masses on sloping snow banks, but the light, and the rain, was uninspiring and I went out into the open terrain to  look for shots. I’d just passed a wide open stretch between the seals when a distant bull, fully 50 yards away, suddenly charged me. The seal came on fast, not too fast for me to run from but I held my ground, figuring that the seal would stop. It didn’t, and at the last second I stuck my rain-coated-covered camera in the seal’s face. It stopped, and fortunately didn’t grab my expensive rain gear, but its wide eyes looked around at me in its expressionless aggressive pose, then turned and shambled off.

look for shots. I’d just passed a wide open stretch between the seals when a distant bull, fully 50 yards away, suddenly charged me. The seal came on fast, not too fast for me to run from but I held my ground, figuring that the seal would stop. It didn’t, and at the last second I stuck my rain-coated-covered camera in the seal’s face. It stopped, and fortunately didn’t grab my expensive rain gear, but its wide eyes looked around at me in its expressionless aggressive pose, then turned and shambled off.

Several of our Mexican passengers had seen the charge and were a bit shaken up, but I assured them that if they stood their ground they’d be ok. I should have added that one also needed a blocking instrument of some kind, too.

As I headed back to our landing zone to assist in loading the zodiacs I saw the same seal charge a short distance towards another person, this time one of our trip leaders. He didn’t have a pole or tripod and the seal kept on coming, knocking him down and biting him close to the knee. He kicked at the seal several times and it moved off, but the bite was a good one and required four stitches. It was a sobering reinforcement of the warnings we’d given our passengers about the dangers a fur seal can pose.

Day 9, Salisbury Plains.

Day 9, Salisbury Plains.

The morning was dark and wet as we off-loaded onto the beach of what is one of the most spectacular beaches for King Penguins. Approximately 60,000 pairs nest on the flats and the hillside, and in good weather, the birds and the ring of mountains surrounding the rookery are stunning. Unfortunately, this morning was not that type of day.